Of the three million students identified as gifted in the United States, a recent NPR article claims, that non-native English speakers or ELL (English language learners) students are by far the most underrepresented. While it is true that non-native English speakers or ELL students are often underrepresented in gifted programs, the article does not address the issues and difficulties posed for gifted 2e kids. In fact, there is no mention of them. For many Gifted 2e parents, the article reinforces the dilemmas with their local district for their 2e kids and why so many seek out homeschooling as an alternative educational option.

Let's start with what the federal law says. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA 2004) requires all U.S. public schools to provide for the special needs for all children, ages three through 21 with disabilities. Additionally, the American Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA) provides safeguards to protect persons with disabilities from discrimination of any kind. Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 provides services to children who may not qualify as disabled under IDEA 2004 but who need additional supports of services. These federal laws apply to all children regardless of nationality, language spoken, or length of residency; and such children are eligible for these services through the public school system.

In theory this may sound good, but what happens in reality for many gifted 2e parents is much more thorny. First, a child needs to be identified as having special needs. This in itself is far from being simple. My son, who is now 10 years old, was born in New York City with special needs, mainly physical ones. He qualified for therapy through Early Intervention (a federally mandated program) as a baby. Once he turned three, however, the medical model of qualifying for services with Early Intervention no longer applied. An educational model applied instead: my son's potential academic achievement were considered. Except at age three, it's very hard to assess and predict the future educational trajectory of a child, especially one with special needs and developmental delays. Even the best psychologists in the country will not administer an IQ (intelligence quotient) test at age three; it's too young for any accuracy.

Cognitive and/or academic aptitude tests, regardless of age, may be given to determine whether a child qualifies for special education or services through a public school system. Oftentimes, though, such tests are based on a particular age and with low ceilings. Furthermore, public school officials who administer such tests may not be skilled in assessing a 2e child. They may have little experience with a child who may be ahead in one aspect but have a deficit in another or one who is not receptive to testing. In the end, parents may seek out private testing. But this is often costly. It's cost prohibitive to those without the financial means or not an option for those without access to private testing in their area. This only serves to further undermine the hurdles for a 2e parent and child.

What complicates matters further is that special needs can vary widely and be slippery to define and to identify. A gifted 2e child usually refers to a child who has above average intelligence and one or more disabilities. But there are exceptions with this definition: some savants such as Kim Peek, for one, who have islands of genius or exceptional abilities despite some severe disabilities. Disabilities (or weaknesses) for 2e children can run the gamut from autism and deafness to dyslexia and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Under IDEA 2004, a special needs student is defined as having: "a disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding or in using language, spoken or written, which may manifest itself in an imperfect ability to listen, speak, read, write, spell, or to do mathematical calculations." Again, it sounds great in theory, but in practice the diagnosing of a disability or a recognition of special needs can be complicated and messy. Many children with dyslexia, dyscalculia, dysgraphic, and/or dyspraxia are never diagnosed or identified. Or where the line is drawn on who is defined as dyslexic and qualifies for services is often fraught with murkiness.

Moreover inconsistencies and unevenness in performance and abilities are hallmarks of 2e children. They may have delays. They may be early bloomers with some developments and/or late bloomers with other developments. Or they may be a mixture of both. They may be highly verbal or have deficits with language skills. They may perform or test well one day, but not the next. They may swing from avoiding situations or experiences to seeking them out. They may seem out-of-sync with others and have trouble coping with their mixed abilities.

Those who go to school may find their special needs or giftedness fly under the radar or go unnoticed. A teacher may be aware a child has special needs but a parent might be unaware. Or the situation may be reversed with a parent suspecting special needs and a teacher not seeing them or being unaware. A gifted 2e child may fluctuate between highs and lows in a particular day and/or subject. Some days a 2e child may seem exceptional while other days the special needs may seem particularly glaring. At times, nothing may seem to fit or work out. Nothing about them may seem linear or sequential like it may appear in comparison with more neurotypical children.

Worse, behavioral issues can often coexist with exceptional abilities. A gifted 2e child may find things easy in one area, but struggle or find things impossible in another area. They may get frustrated, anxious, and depressed from a lack of challenge. In a school setting, a gifted 2e child may spend a large part of their day just trying to hold themselves together and exert an enormous amount of effort doing so. They may suddenly explode with little to no warning. Unwarranted attention for such disruptive behavior and relentless meetings (or phone calls) with school personnel may ensue. Unwittingly, the student's negative behavior may cause a teacher to put blinders on and, counter productively, such negative behavior may outstrip any exceptional abilities the child may have.

To muddy the waters further, gifted education is NOT federally mandated and, as a result, not every state mandates gifted education. Of the states with gifted programs, approximately six to ten percent of the total student population is considered academically gifted. But this figure does not include the number of students who are not tested as gifted or failed to be identified as gifted. It also does not include such states as Massachusetts where a gifted state mandate does not exist or the number of 2e homeschoolers either since the figures are based on data obtained from public school systems. Of the states with gifted programs, some estimate the 2e population to be around 350,000 or .5%, but this seems woefully low.

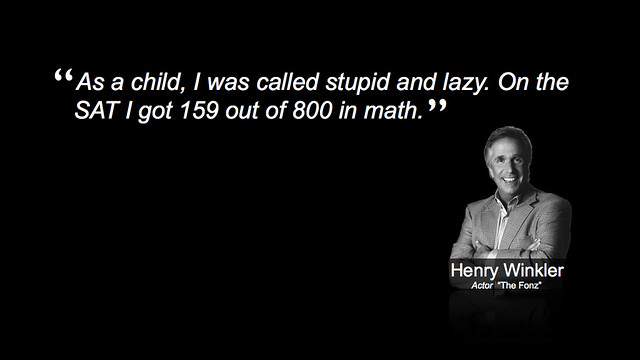

In reality, many 2e children are never identified and muddle through school, never reach their potential, or fall through the cracks -- though despite these obstacles, some persevere through dint of hard work. Take Henry Winkler (an American actor, director, comedian, producer and author). Winkler was born in Manhattan and attended public schools in New York City, but never identified as dyslexic or as a 2e child by either his parents or his teachers. Though he was bright, he thought he was 'stupid.' He didn't read a book until he was 31 years old. Today, however, he's now written 26 books with his Hank Zipzer series and become a spokesman for dyslexia.

Only a handful of schools in the United States offer a curriculum specifically tailored to 2e children. In New York City, which is the biggest city in the US and has the largest public school system in the country, there are very limited options for parents. Many, such as Winkler, are never identified as having special needs or exceptional abilities. Other times, children are identified as having special needs or be gifted but not both. Some gifted schools in New York City may be able to accommodate children on the autism spectrum but not all. In other cities and states, some public schools offer part-time programs for twice exceptional students, but usually there is more demand than there are slots available.

Increasingly, for these reasons and others, many gifted 2e parents opt to homeschooling rather than grappling with a public school system. With homeschooling, they can play to a gifted 2e child's strengths. They can address the social and emotional needs of a gifted 2e child. They can find support and/or provide scaffolding and guidance. And they can provide one-to-one type tutoring opportunities and technology more effectively and efficiently than any other educational setting.

So what makes a 2e child exceptional? I think it's those kids like Kim Peek, Henry Winkler, and everyone in between. And they're by far the most underrepresented.

This is part of the Gifted Homeschooling Forum's blog hop Gifted 2e Kids: What Makes Them Exceptional. For more on GHF's blog hop see: http://giftedhomeschoolers.org/blogs/.

http://giftedhomeschoolers.org/

In theory this may sound good, but what happens in reality for many gifted 2e parents is much more thorny. First, a child needs to be identified as having special needs. This in itself is far from being simple. My son, who is now 10 years old, was born in New York City with special needs, mainly physical ones. He qualified for therapy through Early Intervention (a federally mandated program) as a baby. Once he turned three, however, the medical model of qualifying for services with Early Intervention no longer applied. An educational model applied instead: my son's potential academic achievement were considered. Except at age three, it's very hard to assess and predict the future educational trajectory of a child, especially one with special needs and developmental delays. Even the best psychologists in the country will not administer an IQ (intelligence quotient) test at age three; it's too young for any accuracy.

Cognitive and/or academic aptitude tests, regardless of age, may be given to determine whether a child qualifies for special education or services through a public school system. Oftentimes, though, such tests are based on a particular age and with low ceilings. Furthermore, public school officials who administer such tests may not be skilled in assessing a 2e child. They may have little experience with a child who may be ahead in one aspect but have a deficit in another or one who is not receptive to testing. In the end, parents may seek out private testing. But this is often costly. It's cost prohibitive to those without the financial means or not an option for those without access to private testing in their area. This only serves to further undermine the hurdles for a 2e parent and child.

What complicates matters further is that special needs can vary widely and be slippery to define and to identify. A gifted 2e child usually refers to a child who has above average intelligence and one or more disabilities. But there are exceptions with this definition: some savants such as Kim Peek, for one, who have islands of genius or exceptional abilities despite some severe disabilities. Disabilities (or weaknesses) for 2e children can run the gamut from autism and deafness to dyslexia and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Under IDEA 2004, a special needs student is defined as having: "a disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding or in using language, spoken or written, which may manifest itself in an imperfect ability to listen, speak, read, write, spell, or to do mathematical calculations." Again, it sounds great in theory, but in practice the diagnosing of a disability or a recognition of special needs can be complicated and messy. Many children with dyslexia, dyscalculia, dysgraphic, and/or dyspraxia are never diagnosed or identified. Or where the line is drawn on who is defined as dyslexic and qualifies for services is often fraught with murkiness.

Moreover inconsistencies and unevenness in performance and abilities are hallmarks of 2e children. They may have delays. They may be early bloomers with some developments and/or late bloomers with other developments. Or they may be a mixture of both. They may be highly verbal or have deficits with language skills. They may perform or test well one day, but not the next. They may swing from avoiding situations or experiences to seeking them out. They may seem out-of-sync with others and have trouble coping with their mixed abilities.

Those who go to school may find their special needs or giftedness fly under the radar or go unnoticed. A teacher may be aware a child has special needs but a parent might be unaware. Or the situation may be reversed with a parent suspecting special needs and a teacher not seeing them or being unaware. A gifted 2e child may fluctuate between highs and lows in a particular day and/or subject. Some days a 2e child may seem exceptional while other days the special needs may seem particularly glaring. At times, nothing may seem to fit or work out. Nothing about them may seem linear or sequential like it may appear in comparison with more neurotypical children.

Worse, behavioral issues can often coexist with exceptional abilities. A gifted 2e child may find things easy in one area, but struggle or find things impossible in another area. They may get frustrated, anxious, and depressed from a lack of challenge. In a school setting, a gifted 2e child may spend a large part of their day just trying to hold themselves together and exert an enormous amount of effort doing so. They may suddenly explode with little to no warning. Unwarranted attention for such disruptive behavior and relentless meetings (or phone calls) with school personnel may ensue. Unwittingly, the student's negative behavior may cause a teacher to put blinders on and, counter productively, such negative behavior may outstrip any exceptional abilities the child may have.

To muddy the waters further, gifted education is NOT federally mandated and, as a result, not every state mandates gifted education. Of the states with gifted programs, approximately six to ten percent of the total student population is considered academically gifted. But this figure does not include the number of students who are not tested as gifted or failed to be identified as gifted. It also does not include such states as Massachusetts where a gifted state mandate does not exist or the number of 2e homeschoolers either since the figures are based on data obtained from public school systems. Of the states with gifted programs, some estimate the 2e population to be around 350,000 or .5%, but this seems woefully low.

In reality, many 2e children are never identified and muddle through school, never reach their potential, or fall through the cracks -- though despite these obstacles, some persevere through dint of hard work. Take Henry Winkler (an American actor, director, comedian, producer and author). Winkler was born in Manhattan and attended public schools in New York City, but never identified as dyslexic or as a 2e child by either his parents or his teachers. Though he was bright, he thought he was 'stupid.' He didn't read a book until he was 31 years old. Today, however, he's now written 26 books with his Hank Zipzer series and become a spokesman for dyslexia.

Only a handful of schools in the United States offer a curriculum specifically tailored to 2e children. In New York City, which is the biggest city in the US and has the largest public school system in the country, there are very limited options for parents. Many, such as Winkler, are never identified as having special needs or exceptional abilities. Other times, children are identified as having special needs or be gifted but not both. Some gifted schools in New York City may be able to accommodate children on the autism spectrum but not all. In other cities and states, some public schools offer part-time programs for twice exceptional students, but usually there is more demand than there are slots available.

Increasingly, for these reasons and others, many gifted 2e parents opt to homeschooling rather than grappling with a public school system. With homeschooling, they can play to a gifted 2e child's strengths. They can address the social and emotional needs of a gifted 2e child. They can find support and/or provide scaffolding and guidance. And they can provide one-to-one type tutoring opportunities and technology more effectively and efficiently than any other educational setting.

So what makes a 2e child exceptional? I think it's those kids like Kim Peek, Henry Winkler, and everyone in between. And they're by far the most underrepresented.

This is part of the Gifted Homeschooling Forum's blog hop Gifted 2e Kids: What Makes Them Exceptional. For more on GHF's blog hop see: http://giftedhomeschoolers.org/blogs/.

http://giftedhomeschoolers.org/